Special Feature: The evolution of Motocross GPs

By Alex Hodgkinson on 2nd Dec 15

Motocross GPs have been around as the pinnacle of off-road sport for more than 60 years but the world series has evolved more than anyone could have imagined since TMX was born back in 1977

Lads racing bikes over rough ground had been around for 53-years when TMX first appeared and the FIM stamp of approval ‘World Championship' was already 20-years old – you could add on another five for the ‘European' tag.

The fact is that not one race in any series – 250s were not given their own world status until 1962, while the 125s had been added as recently as 1975 – had ventured outside Europe until the Carlsbad 500GP of 1973 took the fastest riders in the world to Southern California and it was not until 1985 that the FIM top brass discovered the delights of intercontinental Business Class travel outside North America.

South Africa, Argentina and Brazil were the first exotic points of call but since then Japan, Australia, Venezuela, Guatemala, Indonesia, Chile, Mexico, Qatar and Thailand have been added to the list with Malaysia joining the club in March.

World motocross has now reached every continent except for the snowy ones that sit at either axis of the globe and even FIM snowmobiles haven't been there.

However, despite the rapid expansion of recent years, ‘world' motocross continues to be essentially a European phenomenon. Brad Lackey, Danny LaPorte, Chad Parker, Donny Schmit and Bob Moore have grabbed gold for the USA, Greg Albertyn, Grant Langston and Tyla Rattray for South Africa, Shayne King and Ben Townley for New Zealand but the only world champ from outside Europe not to stem from the Anglo-Saxon world was Japan's Akira Watanabe in 1978.

The world of 1977 was one in which Belgium swept both FIM team contests – since 1961 there had been a Trophee des Nations for 250s, while the Motocross des Nations, still far away from having its title anglicised, was strictly for 500s – the class of kings.

Gaston Rahier, not rated highly enough to represent his country in the team events, gave Suzuki and Belgium its only individual champion that year in the 125s but the 250 class belonged to the Soviets as Russian Gennady Moiseev dominated the series along with Ukrainian Vladimir Kavinov, Roger De Coster's reign in the 500s was ended dramatically by an overwhelming Heikki Mikkola as the Finn left Husky to give Yamaha its first big bike title.

Graham Noyce started the summer with second to De Coster at Sittendorf in the Vienna woods but missed several mid-season GPs and never figured on the podium again until Namur in August as he dropped four places in the 500 world rankings from his 1976 rookie fourth. Meanwhile John Banks just missed the series top 10 despite a sensational second moto second to Mikkola at Farleigh Castle on the factory CCM.

With points only awarded to the top 10, Bob Wright, Vic Eastwood and Vic Allan only added six points between them and the best UK result of the year was Andy Roberton's second overall at Farleigh – the Welshman's career best GP result – an effort which earned him no points as he was a 250 graded rider and FIM rules at the time insisted that no-one could score in more than one series. This ruling was blissfully ignored by the world governing body's incompetent staff as they incessantly cocked up the ‘official' tables.

Neil Hudson's rookie year in the 250s brought him 13th in the series, second best Maico to firm owner's son Hans Maisch, after a roll of sevenths, but the positive signs for the following year were already there when the West Country lad took fifth overall at the late season Swedish GP. Rob Hooper and Geoff Mayes tweaked a couple of points too.

The 125s had almost disappeared from the UK adult scene after a few brief years with championship status earlier in the decade but Roger Harvey and Andy Ainsworth, though 15th & 17th in the rankings, were the front men for Husqvarna and Simoni with Pete Mathia on Mike Eatough's EMC machinery just out of the points.

It was a relatively disappointing year for the Brits but that was soon to change...

Hudson returned to Sweden the next year to claim his maiden GP victory on the back of four consecutive podiums as he advanced to fifth in the world while Noyce joined Honda to land three podiums before shattering the old guard in 1979, leading the 500 series nearly all summer to clinch the title with a round to go. Hudson was only headed by fellow new top gun, Hakan Carlqvist, in the 250s and Britain came the closest they had been in more than a decade to winning the Nations at Ruskeasanta, the powerhouse track now covered by the DHL base behind Helsinki airport.

British interest in the 125s hit ground zero with not a single contestant all year but the Irish Free State found enough cash to run a GP just outside Dublin and a teenage Stephen Russell came down from the North to only just miss the points.

Contract wranglings between Maico and Yamaha over the services of Neil Hudson were just the start of British woes in 1980 as Hudson got T-boned out for the year at the first corner in Beuern and Noyce suffered a broken leg. When Kawasaki's domestic teenage whirlwind Dave Thorpe broke too, Britain had lost its entire A team for the Nations on home ground at Farleigh, but the mighty Belgians, who swept the board – Harry Everts (125), Georges Jobe (250), Andre Malherbe (500) and both team contests – got a shock as Dave Watson, the youngster who could not disguise the lilting Ulster accent as he insisted that his Cheshire birth made him English, at least gave the crowd some cheer on a dull September day.

But the 1980s belonged to Britain!

Hudsondefied all Belgian attempts to knock him off in the 1981 250cc finale at Lichtenvoorde in Holland to take the title which should have been his the year before. Noyce rocketed back into contention to narrowly lose the 500 crown in an internal Honda duel with Malherbe and the French GP at Villars-sous-Ecot in April 1982 was another landmark as Dave Thorpe started his first full season with a second place to Malherbe.

By 1984 life in the fast lane had caught up with the first wave of the British revival but Thorpe was the only non-Belgian rider in the mighty HRC troupe, ending the season with a hat-trick of maximum point GP victories to herald two fantastic seasons which led deposed champion Malherbe to declare that David was the hardest rival he had ever faced. Meanwhile Georges Jobe was spitting blood over broken Kwackers and Hakan Carlqvist's stuttering expletives over the now outdated air-cooled YZ490 saw Yamaha sack the man who could have utilised their revolutionary alu-framed water-cooler in 1987/88.

Jonathan Wright and Paul Hunt injected a little UK public interest in the 125s but it was continental youngsters Pekka Vehkonen, Dave Strijbos and John Van den Berk who ended Suzuki's 10-year stranglehold on the class while interest in the 250s faded despite GP wins for Jeremy Whatley and Rob Herring.

Each had the speed to be champion but Jem frequently followed up an overwhelming GP victory with a double DNF a week later and the SA-bred ‘Fish', having headed AMA champ Jeff Ward in the Belle Vue SX, could throw away motos on the last lap when leading by a minute.

With big-bike sales dwindling as suspension failed to keep pace with the savage power of the 500cc two-strokes, the Japanese factories withdrew one by one from the class of kings to concentrate their efforts on the 250s, and, aided by a bearded Italian entrepreneur by the name of Giuseppe Luongo, the FIM was persuaded by hook or by crook to declare ‘premier' status to the quarter-litre class from 1992.

The fastest kids on the GP block did indeed gather in the upgraded series, however you can lead a horse to water but you can't make it drink, and the 500s, outlaws in the USA, refused to die on the world stage as the fans flocked to see the new generation of four-strokes which emerged in the 1990s.

The CCM efforts at Farleigh in 1977, the Hallman-Eneqvist Yamaha of Bengt Aberg and the KSI Honda of Marty Moates a year later, had been the swansong of the four-strokes, which hadn't won a title since Jeff Smith in 1965 and not even a GP since Dave Nicoll in 1969. But the roaring nineties turned the tide.

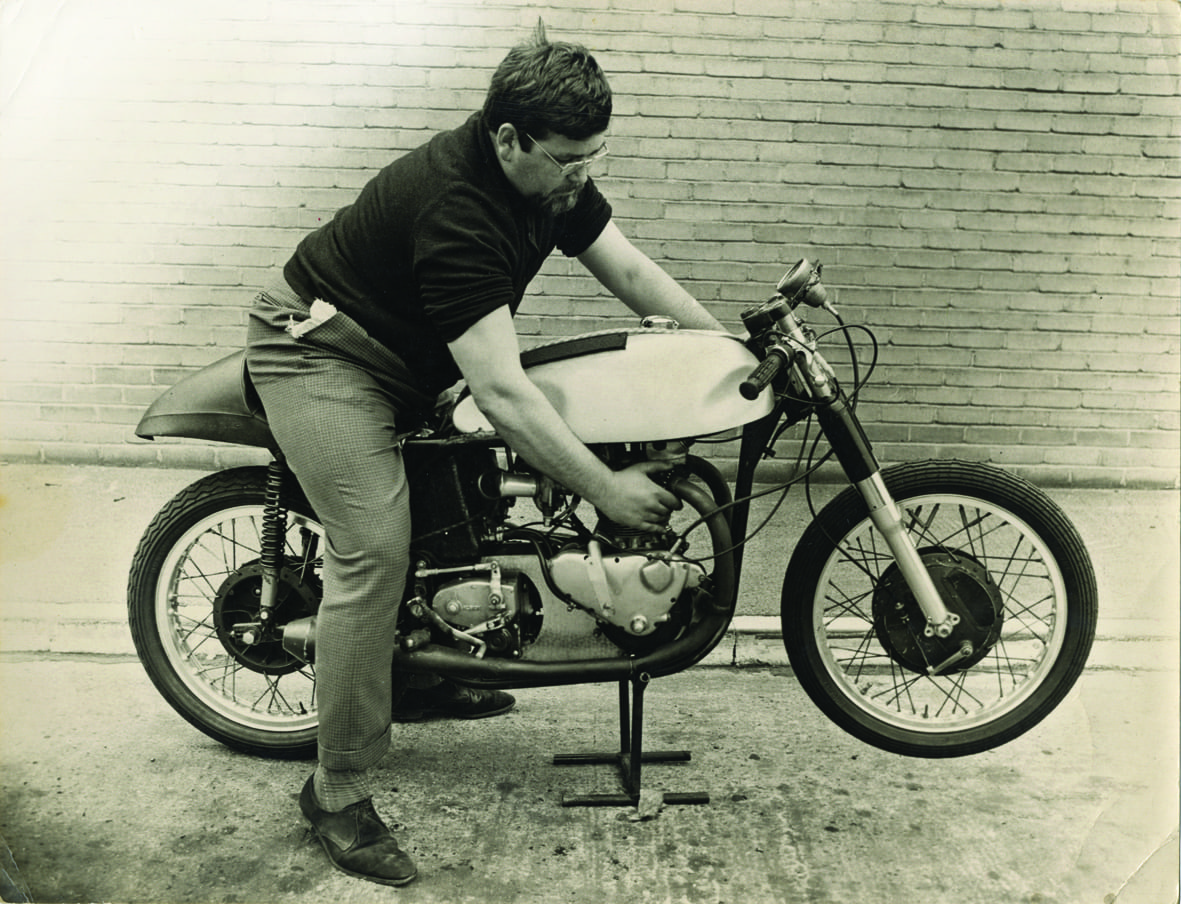

CCM's justified claims that four-strokes should be granted a higher engine volume limit against the more efficient two-strokes was continually rejected in the 1970s and it was only by slight of hand, or rather foot, that a future FIM race director saved the Bolton factory getting caught for using a 580 at the 1977 Farleigh GP.

Italybrought the four-stroke renaissance in 1991 with Jacky Martens joining Husky and the Vertemati brothers refining Husabergs for first Walter Bartolini and then Joel Smets.

Martens took the ‘500' title in 1993 and Smets was king in 1995-97-98 – the battles with the private CR500s and screaming factory 380 KTMs enthralling hard-core fans.

But it was Yamaha which made four-strokes truly fashionable again as it introduced the YZ400F in 1997. The marque took a caning at first but by 1999 Andrea Bartolini brought Yamaha the title and other Japanese companies were on the case.

Japanese development philosophy entails at least a six-year plan and the new millennium was in full swing before even Honda, who had upheld four-stroke pride against the strokers in road-racing 40-years earlier unveiled the CRF450R. By the middle of the decade Red had gone holier than thou withdrawing the supposedly ‘dirty' two-strokes completely from its range.

It was 2004 before Suzuki starting racing four-strokes off-road and Kawasaki took even longer in the premier class but, once they were there, the European first line of defence was left in the hands of KTM.

Britain's GP fortunes waned dramatically in the 1990s in comparison to the previous decade when half a dozen Brits could finish top 10 on any given day as big bikes ruled – Kurt Nicoll, the eternal number two, Laurence Spence, Mervyn Anstie and Mark Banks could all race up front in the 500s, while Jeremy Whatley, Rob Herring and Andy Nicholls each outran the world on their day in the 250s and matched the best when they stepped up to 500s. ‘Kaptain' Kurt even surprised critics when he joined the 250 ‘premier' class, winning the GP on the day at Gaildorf as Greg Albertyn defeated Stefan Everts for the second straight year.

But Everts, Albee, Chad Parker, Donny Schmit, Sandro Puzar, Bob Moore, Marnicq Bervoets and Yves Demaria were the ‘names' as marketing took over the sport from the FIM, the PR machine elevating the 250s in the eyes of casual onlookers with a massive expansion of outside sponsorship in the final days of tobacco and alcohol advertising and the early days of energy drinks.

Two more bright youngsters had emerged from the UK youth scene in the late 1980s, indeed both Paul Malin and James Dobb were an integral part of the ACU Nations team in 1990 and ‘Maler' broke a record which had stood for 37 years when he won the French 500GP to take over from Jeff Smith – the first teenage superstar back in the 1950s – as the youngest big bike winner of all time.

The Kawasaki switch to the 250s did Maler no favours as politics and backbiting destroyed his confidence when the results didn't come while Dobb was a starry eyed kid who jumped at the chance to race Stateside.

Each wasted a significant part of their career but each was to rebound in unusual circumstances, ironically in the class where Brits had never previously figured... the 125s.

That historic day when ‘Maler' sensationally led the British defeat of the ‘invincible' Yanks at the 1994 Nations was the impetus to race 125s full-time and the voice of mxgp.tv had the hillsides on fire with his GP victory the following summer at Foxhill before an astounding 1996 season when he raced Sebastien Tortelli wheel-to-wheel all summer for the 125cc world crown.

By 1997 Dobber was back in Europe and, after occasional leaderboard years with Rob Hooper's Suzuki team and Honda UK, he finally got factory equipment with KTM in Y2K.

It was perfect timing as Mattighofen stepped up to dominate the class with Dobb, Grant Langston and Kenneth Gundersen but it was another factor which put James on top of the world.

Back in 1992/1993 Giuseppe Luongo had used his marketing influence to bury ‘tradition' with the sad three short moto experiment – more starts were allegedly better for TV, but short motos placed undue importance on a good gate – and by Y2K the Italian entrepreneur, his word law at the FIM since he used his skills as campaign manager to sell delegates a new FIM president, saw the possibilities of multiple class GPs.

There had already been double-headers at Suzuka in Japan in 1991/92 but John Horler must be credited with developing the idea at Foxhill from 1995. Having acquired the ‘rights' to the 125s and 500s Luongo took it a step further in Y2K.

Triple headers were run at Valkenswaard, Foxhill, Francorchamps, Grobbendonk and Ettelbruck that year, and the outside world – in particular Dorna – took notice.

The Spanish rulers of MotoGP had cash to spare after the Lawson-Rainey-Schwantz-Doohan era and opened the cheque book for a world they never understood. "I could not refuse," Luongo has told me since. "They offered me a price many times what the series was worth."

Dorna immediately enforced its MotoGP recipe on a series of triple headers but an 11am start, one moto per class and increased admission did not go down well with the fans. They never got the support of the riders either, despite dramatic increases in prize money through the field, and, after three years of losing a million each weekend and reducing the series to just 12 GPs as promotors gulped at the fees they were expected to invest, Dorna was desperate to off-load MXGP.

Luongo, having taken his entourage to Supermoto in the interim, bought back his first love for a song, and the rest is history as he has brought motocross to the living room worldwide and offered manufacturers a platform for their product.

But, back to 2001. That single moto format was hated by most competitors, particularly anyone who went down at turn one, but James Dobb and Mickael Pichon revelled in it. Each of them called in their US SX experience to know what was required. Each could raise their heartbeat from 120 to 200 when the 10 second board was turned and most of the races were over within three laps as they disappeared into the distance while their rivals maintained the ‘traditional' approach of settling into a rhythm to prepare for a decisive final charge. GP motocross had changed overnight and the reduction from 40+2 to 35+2 to 30+2 in more recent years has meant it stayed.

Mid-1990s hotshot Everts had gone through a traumatic couple of years with injuries at the turn of the millennium and was no match speedwise for Smets in his first couple of years at Yamaha but that single moto format, with so few races to pull back a zero score brought the consistent S72 the title against the all-action ‘Flemish Lion'.

By 2003 the factories were calling for more exposure for their four-stroke future and MXGP was born as the best of both worlds met. Pichon ran rings round everybody at the first three rounds on his Suzuki stroker but from round four at Montevarchi the four-strokes took command.

FIM race director, Dave Nicoll, would deny it, but tracks were prepared to ruin two-stroke momentum in the turns and a brainstorm by Michele Rinaldi put Everts back on course to become a legend.

The Belgian needed 10 minutes to settle into his rhythm if he was to avoid arm-pump and of course by then Pichon was out of sight but I stood ear-wigging post race at the Everts camper door in Teutschenthal as Michele and brother Carlo proposed the solution. Stefan would race the 125s on Yamaha's 250F to ‘warm up' and it worked. He could play with the kids and still win and two races in rapid succession was no problem for Stefan – his body toned by a strict fitness regime. He only lost one more race all year in either class and even ended the season with three wins in one day at Ernee as he took the 650s too.

The Everts era has been superceded by the dominance of Toni Cairoli and even Luongo's most ardent critics cannot argue that he has created a pyramid to maintain a solid supply of fresh talent. Watch the 125 Euros next time you get the chance if you doubt it.

Champions in 2015 Romain Febvre and Tim Gajser did not emerge from nowhere. On the morning of the Gaildorf GP in 2011 when Ken Roczen took the MX2 world title and Toni Cairoli his second MXGP for KTM the virtually unknown French privateer collected the EMX2 title, and the following summer at Matterley the Slovenian added the EMX125 crown to titles in the 65 and 85 classes.

TMX has now kept you informed on the world scene for 38 years and when the lights are turned on in Qatar in February we will be there again to give you the lowdown on what is happening all the way through to the 2016 Glen Helen finale and the years beyond.

Here's to the next 2000 issues...

FOR MORE HISTORICAL CONTENT, MAKE SURE YOU GRAB A COPY OF TMX'S 2000TH EDITION!